![]()

Click on these links for a "hot lap" of the TZ350 and 250 Website:

The publishing of this article would not have been possible without the permission of the author, Alan Cathcart. (Thanks Alan.)

YAMAHA OW48R: Piston Port Prowess

by Alan Cathcart.

Although Kawasaki was the

first to challenge for 500cc GP honours with a two-stroke design, in the form of

the privateer H1R triple which Kiwi Ginger Molloy took to a runner-up slot

behind Agostini’s ubiquituous MV Agusta in the 1970 World Championship, it was

Yamaha which led the way in mounting a fulll-on factory effort to overturn the

established four-stroke order of merit in road racing’s premier class. For it

was 1973 which saw the advent of the 0W19 ridden by Jarno Saarinen to victory in

its very first race at Paul Ricard in the spring of that year - the world’s

first four-cylinder 500cc two-stroke GP racer, and the first Yamaha to bear the

YZR500 generic tag still borne today by Garry McCoy’s and Max Biaggi’s works V4

machines.

Although Kawasaki was the

first to challenge for 500cc GP honours with a two-stroke design, in the form of

the privateer H1R triple which Kiwi Ginger Molloy took to a runner-up slot

behind Agostini’s ubiquituous MV Agusta in the 1970 World Championship, it was

Yamaha which led the way in mounting a fulll-on factory effort to overturn the

established four-stroke order of merit in road racing’s premier class. For it

was 1973 which saw the advent of the 0W19 ridden by Jarno Saarinen to victory in

its very first race at Paul Ricard in the spring of that year - the world’s

first four-cylinder 500cc two-stroke GP racer, and the first Yamaha to bear the

YZR500 generic tag still borne today by Garry McCoy’s and Max Biaggi’s works V4

machines.

That first Yamaha four, measuring 54 x 54 mm, set the format for others which followed over the next decade, with horizontally split crankcases, four transverse in-line piston port cylinders, each with four transfer ports and a single exhaust, and two separate crankshafts utilising 180-degree crank throws, geared together and driving the six-speed transmission via a layshaft located behind the cranks. But Saarinen’s tragic death in May ’73 in the 250cc Italian GP at Monza, after having won two of the season’s first three 500cc GP races on his twin-shock factory machine, set Yamaha’s world title foray back a couple of years, with MV retaining the championship in both ‘73 and ‘74. But for 1975 the Japanese factory finally achieved its prized goal, taking the 500cc world title with the monoshock OW26, complete with side-loading extractable gearbox, thanks to its new recruit from the rival MV Agusta team, Giacomo Agostini.

Originally, these early Yamahas employed reed valves in order to cure the perennial problem of piston ported two-strokes, namely their symmetrical port timing which leaves just as much time for an incoming charge of mixture to escape via the exhaust ports, as to pump it in from the carbs. The growing dominance of the Suzuki RG500, whose rotary-valve design’s assymetrical timing meant it didn’t suffer from this handicap, persuaded Yamaha to take a year off from 500cc GP racing in 1976, in order to develop an all-new four-cylinder machine code-numbered OW35, which broke with the company’s four-year tradition of promoting rideability as opposed to the pursuit of outright power, by jettisoning the reed valves in order to remove their inherent barrier to clean intake flow, and thus top end numbers. Powerjet carbs also made their debut, on a bike which for the first time adopted the short-stroke 56 x 50.6 mm engine dimensions of later 500 Yamahas. But even in the hands of Steve Baker, Johnny Cecotto and Ago, the OW35 was no match for the Sheene/Suzuki combo - a fact the unfortunate Baker paid for by being dropped from the team for the following season, in favour of Yamaha’s new American superstar, Kenny Roberts.

Together with teammates Takazumi Katayama and Johnny Cecotto, Roberts had the use of the first motorcycle to adopt one of Yamaha’s trademark breakthroughs in two-stroke engine design, the electronically controlled YPVS system, whose variably operated cylindrical valve effectively lowered the height of the exhaust port to improve tractability at low rpm, while raising it to increase peak power at higher engine speeds. This was progressively introduced to the OW35 during the early part of the 1978 season, in which Roberts won four of the nine championship rounds, so that by the time of the final GP on Germany’s 14-mile/23 km. long Nurburgring circuit, in which he finished third, Roberts had done enough to earn his King Kenny crown by clinching the first of his hat-trick of world titles for Yamaha.

In spite of missing the opening Venezuelan GP of the 1979 season thanks to an injury occasioned while testing in Japan, Roberts doubled-up in championship crowns that year on the updated version of the YZR500, code-numbered OW45, only minor suspension changes on which distinguished it from the OW35 of 1978. But in spite of winning five GP races that season en route to his and Yamaha’s second world championship in a row, King Kenny had been pushed hard all the way by Suzuki’s new Italian star, Virginio Ferrari, whom Roberts realised would pose a potent threat for the coming season. So, for 1980 and his attempt to win a hat-trick of world titles, Roberts kept pressuring Yamaha to deliver more power from their piston port motor, as a counter to the now much faster square-four rotary-valve Suzukis.

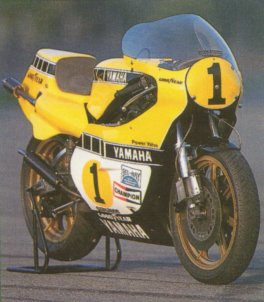

While unable initially to do

so, Yamaha instead concentrated on reducing the weight of the new OW48,

replacing the tubular steel cradle frame used on all four-cylinder Yamahas

hitherto with a much lighter square-section aluminium tubular chassis, painted

black like the steel frame it replaced in order to deflect attention in the

paddock (it didn’t!), but with the engine carried lower in the frame, and with

increased front end weight bias, both as Roberts had requested. Engine

modifications were initially restricted to the introduction of a new guillotine

powervalve instead of the cylindrical one, revised porting and a choice of both

flatslide and cylindrical-slide carbs varying from 3mm and 36 mm to 38mm in

diameter, depending on the circuit. Fitted with the larger of these, the 56 x

50.6 mm piston-port engine was claimed to produce 120 bhp at the crank,

translating to 102 bhp at the rear wheel, at 11,500 rpm, while for 1980 Yamaha

introduced a detuned customer copy of Roberts’ ‘79 title-winner for sale to

privateers as a counter to the RG500 Suzuki, which for half a decade had been

packing 500cc GP grids. The steel-framed TZ500G came with 34mm Powerjet carbs,

side-loading gearbox and a cylindrical powervalve, which was however

mechanically driven, rather than electrically as on the works machines.

While unable initially to do

so, Yamaha instead concentrated on reducing the weight of the new OW48,

replacing the tubular steel cradle frame used on all four-cylinder Yamahas

hitherto with a much lighter square-section aluminium tubular chassis, painted

black like the steel frame it replaced in order to deflect attention in the

paddock (it didn’t!), but with the engine carried lower in the frame, and with

increased front end weight bias, both as Roberts had requested. Engine

modifications were initially restricted to the introduction of a new guillotine

powervalve instead of the cylindrical one, revised porting and a choice of both

flatslide and cylindrical-slide carbs varying from 3mm and 36 mm to 38mm in

diameter, depending on the circuit. Fitted with the larger of these, the 56 x

50.6 mm piston-port engine was claimed to produce 120 bhp at the crank,

translating to 102 bhp at the rear wheel, at 11,500 rpm, while for 1980 Yamaha

introduced a detuned customer copy of Roberts’ ‘79 title-winner for sale to

privateers as a counter to the RG500 Suzuki, which for half a decade had been

packing 500cc GP grids. The steel-framed TZ500G came with 34mm Powerjet carbs,

side-loading gearbox and a cylindrical powervalve, which was however

mechanically driven, rather than electrically as on the works machines.

By now riding at the peak of

his powers, Roberts blitzed his Suzuki factory rivals on the aluminium-framed

OW48 at the start of the 1980 season, to win the first three races in succession

of the 1980 season, in Italy, Spain and France. In doing so, he also humbled his

Yamaha teammates, the TZ500G and RG500 mounted privateers and the new KR500

Kawasaki of Kork Ballington, but for the next race at Assen - a wet one which

marked the first GP success for a Yamaha four-cylinder customer bike, when Jack

Middleburg won on home ground on his TZ500, albeit employing a Bakker frame and

RG500 forks - Roberts was provided with an update of his winning machine, the

OW48R, with the ‘R’ standing for reverse cylinders. That’s because on this bike

the two outer cylinders were turned around 180 degrees to point forward, thus

permitting a straight run to their pair of now rear-facing exhausts.

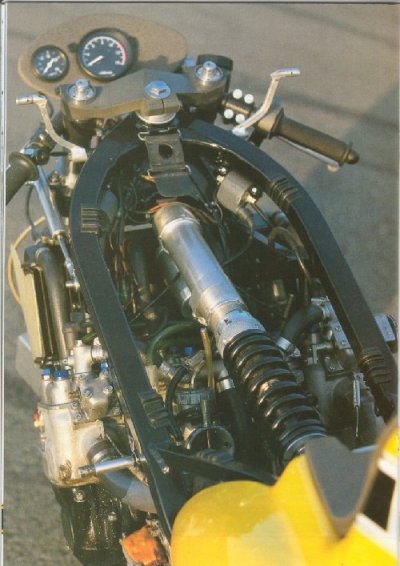

This

increased midrange power by no longer reducing the amplitude of the resonant

pressure waves in the pipe, while also providing more space for the two inner

cylinders’ exhaust run; by now, Yamaha’s transfer port design needed stronger

suction for top end power, requiring fatter exhaust expansion chambers, which

took up more space. The new engine layout meant that one of the new, bulkier

exhaust pipes no longer had to be threaded through the chassis to exit on the

opposite side from the other three, warming the flow of incoming air to the

rear-facing carbs as it did so, as well as overheating the long rear monocross

shock positioned above the engine. These modifications enhanced top end power by

an extra 7 bhp, on a bike originally employing differential carburation with a

pair of 36mm flatslide carbs on the outer cylinders, and two 34mm ones on the

inners.

This

increased midrange power by no longer reducing the amplitude of the resonant

pressure waves in the pipe, while also providing more space for the two inner

cylinders’ exhaust run; by now, Yamaha’s transfer port design needed stronger

suction for top end power, requiring fatter exhaust expansion chambers, which

took up more space. The new engine layout meant that one of the new, bulkier

exhaust pipes no longer had to be threaded through the chassis to exit on the

opposite side from the other three, warming the flow of incoming air to the

rear-facing carbs as it did so, as well as overheating the long rear monocross

shock positioned above the engine. These modifications enhanced top end power by

an extra 7 bhp, on a bike originally employing differential carburation with a

pair of 36mm flatslide carbs on the outer cylinders, and two 34mm ones on the

inners.

The only problem was that the new engine would not fit in the aluminium chassis which Roberts had now dialled in to his satisfaction - so for its first race at Assen, the OW48R sported the old steel frame. This however produced severe handling problems, so that the best Kenny could do in qualifying was fifth on the grid for the wet race, from which he retired with a slow puncture. At the next race a week later at Zolder he managed a third place rostrum finish in a race won by Suzuki-mounted Randy Mamola, who by now was closing on Roberts’ points lead in the title chase - so for the next round in Finland, Kenny discarded the reverse cylinder bike in favour of the early-season alloy-framed OW48, which he rode into second place behind Wil Hartog’s Suzuki. By the time of the British GP at Silverstone in August, the aluminium chassis had been modified to accept the reverse-cylinder motor, but Kenny still used the OW48 to ride to second place there behind Mamola. Finally, in the last GP of the season at the Nurburgring, he used the alloy-framed reverse-cylinder bike to beat Mamola to the line for fourth place in a race won by Marco Lucchinelli, and thus achieve the coveted hat-trick of World Championships - a feat that only Wayne Rainey (on a Team Roberts Yamaha!) and Mick Doohan have emulated in the modern era of two-stroke GP racing.

It had been a close run

thing, though, with the increased performance of the rotary-valve Suzukis

providing a lesson that Yamaha felt they needed to learn in order to build on

their world title success and provide a bike for Roberts to keep winning with.

Accordingly, for 1981 they produced the first of their short run of disc-valve

500s, the square-four OW54 - leaving the alloy-framed, reverse-cylinder OW48R

factory bikes to provide support for Roberts in defending his title, in the

hands of Christian Sarron, Marc Fontan, Barry Sheene, Sadao Asami, Boet van

Dulmen and Michel Frutschi. It was ‘Den Boet’ who scored the best result for

these semi-works entries, with second place in another wet Dutch TT at Assen in

‘81, while for 1982 Yamaha produced a customer replica of the reverse-cylinder

bike for privateer sale under the TZ500J label, though with a steel chassis and

mechanical powervalve. But by now the disc-valve Suzuki’s day had dawned again,

with successive world titles for the Team Gallina riders Marco Lucchinelli and

Franco Uncini, while Yamaha desperately searched for a suitable design with

which to counter their rivals’ pre-eminence. When it came, in 1984, the OW76

which allowed Eddie Lawson to regain Yamaha’s coveted world title did so by

returning to the company’s previous reed-valve concept, this time with

crankcase-mounted induction and more sophisticated electronics. The day of the

piston port four-cylinder Yamahas which had achieved so much success over a

decade of development was over - a success which culminated in the third of

Kenny Robert’s World Championship crowns in 1980, the high point of the piston

port era of Grand Prix racing.

It had been a close run

thing, though, with the increased performance of the rotary-valve Suzukis

providing a lesson that Yamaha felt they needed to learn in order to build on

their world title success and provide a bike for Roberts to keep winning with.

Accordingly, for 1981 they produced the first of their short run of disc-valve

500s, the square-four OW54 - leaving the alloy-framed, reverse-cylinder OW48R

factory bikes to provide support for Roberts in defending his title, in the

hands of Christian Sarron, Marc Fontan, Barry Sheene, Sadao Asami, Boet van

Dulmen and Michel Frutschi. It was ‘Den Boet’ who scored the best result for

these semi-works entries, with second place in another wet Dutch TT at Assen in

‘81, while for 1982 Yamaha produced a customer replica of the reverse-cylinder

bike for privateer sale under the TZ500J label, though with a steel chassis and

mechanical powervalve. But by now the disc-valve Suzuki’s day had dawned again,

with successive world titles for the Team Gallina riders Marco Lucchinelli and

Franco Uncini, while Yamaha desperately searched for a suitable design with

which to counter their rivals’ pre-eminence. When it came, in 1984, the OW76

which allowed Eddie Lawson to regain Yamaha’s coveted world title did so by

returning to the company’s previous reed-valve concept, this time with

crankcase-mounted induction and more sophisticated electronics. The day of the

piston port four-cylinder Yamahas which had achieved so much success over a

decade of development was over - a success which culminated in the third of

Kenny Robert’s World Championship crowns in 1980, the high point of the piston

port era of Grand Prix racing.

Alan Cathcart

03/23/08 06:37 AM +1000

This website © Greg Bennett 2002.

Text and images used in this article © Alan Cathcart 2000